The Sherrill-Roper engine

Source: The Popular Science Monthly, Vol XVIII, p. 335

Date: Nov, 1880 to April, 1881

Title: Domestic Motors - The Sherrill-Roper engine

Sherrill-Roper engine

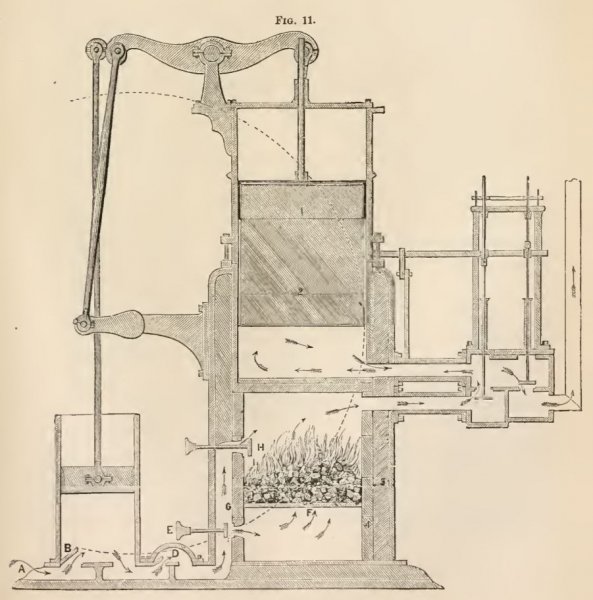

One of the best of this class of motors (hot air engine) made for power purposes is the Sherrill-Roper engine, shown in section in Fig. 11. The manner of using the heated air in moving the piston differs somewhat from that employed in the Ericsson engine, the Rider Engine or the Stirling engine, being more nearly like that in which steam is used in the steam-engine.

The furnace is airtight, the air drawn from the atmosphere being forced through and over the fire, and the expanded air and products of combustion being admitted to the cylinder through valves worked by the engine in a way entirely similar to the admission of steam in the steam-engine.

The cylinder is placed over the furnace, from which it is separated by a partition of iron faced with fire-brick upon the furnace-side. This furnace is lined with fire-brick upon all sides except the bottom, making a very durable construction, as there is nothing exposed to the direct action of the fire, to burn out.

The air is drawn from the atmosphere by the upward movement of the piston in the small cylinder at the left, through the valve B, and on the down-stroke of this piston is forced through the channel G into the furnace. The valves H and E regulate the amount passed over and through the fire.

The heated air and products of combustion are admitted into and exhausted from the cylinder through the puppet-valves, shown in the chamber to the right of the engine. A steady gradually diminishing pressure is exerted against the piston by these heated gases, and drive it to the upper end of the cylinder. The exhaust-valve then being opened by the mechanism of the engine, the piston descends by atmospheric pressure, forcing the gases out into the air.

While the power-piston is making its downward stroke the supply-piston draws in a fresh charge of air, which is forced into the furnace during the up-stroke. A fly-wheel makes the motion of the engine smooth and uniform.

The power-piston consists of two shells, the upper one turned true to fit the bored portion of the cylinder, and the lower one fitting it loosely. This latter protects the first portion from direct contact with the heated gases, and, as the upper part of the cylinder does not become overheated, a water-jacket is not needed.

As the furnace is a closed compartment, the engine must be stopped in order to replenish the fire. This is not so much of an inconvenience, however, as it would at first sight appear, as one firing in the morning and another at noon, when the motor is running continuously ten hours a day, are all that are required.

The machine is compactly built, and runs with very little noise. It is made in sizes of from one and a half to seven horse-power, at prices ranging from something less than five hundred to one thousand dollars.

According to the statement of the manufacturers, the engine is exceedingly economical of fuel, the one and-a-half horse-power using but forty pounds of coal per day of ten hours, and the three-and-a-half, eighty pounds. This is but a little over two pounds per horse-power per hour, a result attained in the steam-engine only in the larger-sized and most perfectly constructed machines.